The Protein Paradox – how much is too much and where should it come from?

Meat to meet global dietary requirements

The amount of food we produce today will be insufficient to feed a global population of almost 10 billion people in 2050. Meat is an important source of nutrition for many people around the world, and a leading source of protein in many diets. The UN Agricultural Outlook 2025-2034 report released last month estimates that per capita consumption of animal source foods will increase 6% globally by 2034. This trend is anticipated to be most pronounced in lower middle-income countries where intake may rise by as much as 24%, fuelled by factors including rising disposable incomes, changing dietary preferences, and urbanisation.

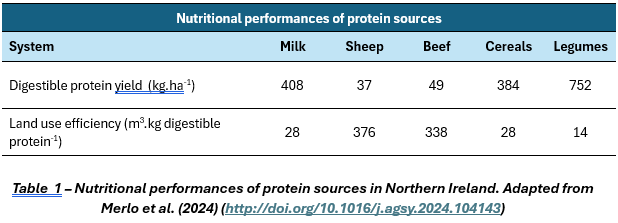

Increasing livestock farming in order to meet this growing demand for animal-sourced foods will undoubtedly cause significant environmental impact through greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, biodiversity loss, water pollution, and land use. A 2024 study by Merlo et al. into farming practices in Northern Ireland confirmed that beef and sheep production have the highest emissions of greenhouse gases per unit of protein versus other outputs, including milk, cereals, and legumes. Livestock farming is also an inefficient route to producing sufficient protein to support the growing population. Merlo et al.’s work also revealed that legumes yield more digestible protein per hectare than any other product studied, around 752 kg/ha. In contrast, beef and sheep meat yield the lowest amount of digestible protein per land area, generating a meagre 49 kg/ha and 37 kg/ha, respectively.

Crucially, there are also health concerns associated with excessive consumption of red and processed meat, including cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, as well as certain cancers such as colorectal.

Here in the UK, there is growing recognition of the impact meat consumption can have on the environment and human health, and consequently, the national food strategy recommends a 30% reduction in meat consumption by 2032. Whilst per capita meat consumption in the UK is now at its lowest levels for 50 years, some demographics are bucking this trend. A study by UK environmental charity Hubbub revealed that young men (aged 16-24) are eating more animal-derived protein now than they did 12 months ago. Almost 40% are eating meat daily, with a similar number unwilling to cut back further. So why are certain populations ignoring advice and upping meat consumption rather than choosing to cut back?

The Protein Megatrend

‘Protein’ is a health and wellness megatrend that has emerged over recent years. Once associated primarily with bodybuilders, high-protein diets are now adopted by a growing proportion of the general population, and are increasingly considered synonymous with health and wellness. Protein can support an increase in muscle mass, it can improve bone density, and contribute to a feeling of fullness, potentially aiding weight management. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for protein is a modest 0.8g of protein per kg of body weight. According to the British Nutrition Foundation, this equates to about 45g of protein a day for the average woman, and ~ 56g for the average man. Whilst higher levels are recommended for specific populations, it seems many of us are consuming protein at levels well above the RDA guidelines. Research by Ocado Retail shows social media searches for ‘high protein’ more than doubled this year, while searches for ‘protein-rich’ increased by 85%. Currently, on average in the UK, men are eating about 85g and women about 67g of protein a day.

How much protein is too much?

There is ongoing debate regarding optimal protein consumption levels. Current recommendations are based on the minimum protein we need to prevent malnutrition, and many argue that 0.8 g/kg/day is too low, particularly for populations such as the elderly who experience an age-related progressive loss of muscle mass and strength. A new technique for establishing protein needs, termed the indicator amino acid oxidation method, has been developed. Using this approach, the minimum protein intake for humans to “thrive” (not just “survive”) is closer to 1 – 1.2g/kg/ day. By this metric, average UK protein consumption levels seem more appropriate. For gym-goers, consumption should be towards the upper end of that range, but anything above the 1.2g may be excessive. Having recently joined the gym, and taking into account the fact I’m a female in my 40s trying to maintain muscle mass and strength (to keep up with my sons who seem to have boundless energy!), I have been recommended to aim for 100g of protein per day. Whether this is excessive or appropriate is unclear to me at this time, but it certainly is well above my regular consumption levels. So, how can I achieve this? Is animal-sourced protein the best option?

Not all proteins are made equal

Animal-sourced proteins are generally considered to be of higher quality than their plant-derived counterparts. Whole plant-based foods typically exhibit slow or reduced digestibility and suffer from source-specific deficiencies in essential amino acids such as lysine. And when it comes to animal protein, consumers are increasingly conscious of where protein comes from, and this is translating into a clear preference for whole foods versus ultra-processed alternatives. So whilst turkey, beef, and pork sales have increased by 5.2 %, 3.0 % and 1.4% year-on-year, sales of meatless burgers have declined by 5.79%. Consequently, some key players in the alternative meat sector are struggling to survive. Beyond Meat’s net revenues declined by almost 20% last year, with US volume sales down 24.2%. Similarly, Neat Burger, a vegan burger company backed by Sir Lewis Hamilton and Leonardo DiCaprio recently entered liquidation after incurring £8 million in losses.

Plant-derived proteins are obviously still favoured by many consumers for health, ethical, and/or environmental reasons. Research clearly demonstrates that switching the average diet to the eating pattern recommended in the UK government’s Eatwell Guide, which is more plant-based, would significantly improve health outcomes and reduce the environmental footprint of our diet. Incorporating more beans, lentils, nuts, and other plant-based proteins would be a healthy way to get some of the protein, but there remains scope for innovation to enhance the potential of plant proteins.

Innovating to boost plant protein potential

Several start-ups are striving to boost the quality and uptake of plant-based proteins; some of the more innovative examples are profiled here:

- Finnish start-up Happy Plant Protein has developed a unique process based on extrusion technology to deliver high-quality, customizable plant proteins with high-protein and high-fibre levels. They claim their approach allows food manufacturers to create ‘superior plant protein in a cost-effective and environmentally friendly way that fits seamlessly into their existing production lines’.

- London-based startup THIS has launched THIS Is Super Superfood, which it describes as a “next-generation” plant protein to compete with tofu and tempeh. It meets customer demand for minimally processed whole foods, containing fava bean protein, a range of seeds, and vegetables to offer consumers a protein rich in fibre, omega-3, and iron, and contribute to your five-a-day.

- Protealis (Belgium) has developed leguminous crop seed treatments to help EU farmers grow more plant-based proteins locally. Through the combination of breeding technologies and proprietary seed coatings, the company is enabling farmers to create new opportunities, overcome protein deficit, as well as offer local sourcing options for the growing number of producers of meat and milk alternatives.

- US-based ERGO integrates DNA sequences from complex animal proteins into plant cell lines for protein production. Through genetic optimisation and mass-scale cultivation, the company generates protein-rich plant biomass efficiently. These proteins maintain their functional properties, enhancing taste, texture, and aroma in end products.

At Strategic Allies, our project managers (PMs) get to work on a wide variety of projects and value the rich variety of subjects and technologies they learn about as part of their role. But certain ‘passion projects’ really capture our imagination and drive a natural curiosity to discover more. Sustainable food systems is an area I’ve been captivated by since my first project on this topic over 12 years ago. Since then, I’ve become a Mum, and my scientific curiosity is now joined by a desire to feed my family nutritious food which is both good for them and good for the planet. I have worked on several projects pertinent to this field that aim to improve the quality of foods or improve the resilience of the food system in a world under constant environmental and geopolitical threat. I’m proud that as a business, we have developed significant know-how and experience in this area and would love the opportunity to apply this to more projects in the future. So please reach out if you are an organisation in need of such support, or indeed are a technology owner with a solution that helps address issues pertaining to food system security. This is one clear example of a problem requiring a collaborative response to make an impact.